Contents

Introduction

Tackling accessibility is a multi-stage approach. Often the most difficult part is not the remediation of issues but instilling a culture where those issues are caught before they reach any backlog.

The causes of accessibility issues

When we talk about accessibility we are generally talking about the barriers which are placed in front of people wanting to complete a task.

For the most part, on the web at least, these barriers can be fixed in some way or other. So we have to examine if this is the case, then why are so many websites still inaccessible when accessibility has been on the professional radar for so long?

The likely cause is unfortunately related to the processes which are involved in the building of those products.

This can take several forms:

- lack of awareness

- deferring responsibility

- assumed cost of implementation

- assumed impact on deadlines

- accessibility as a checkbox item

- reliance on out-of-the-box automation

- lack of support from processes

This needs to be managed by the delivery leads on a project to ensure that both the stakeholders and wider team are aware of the need to prioritise accessibility.

Lack of awareness

This can take a couple of forms, a lack of knowledge or a misunderstanding of the principles.

It might be that no-one has ever broached the subject of accessibility before. This is the easiest blocker to fix as it probably means there are no preconceived ideas, so some upskilling may be all that is needed.

Sometimes it might be that there is a misunderstanding of what disability means or who it affects. Let's examine a couple of the common misunderstandings:

“None of our users are disabled”

Well 1 in 5 people in the UK are disabled, so that is unlikely.

Check DfE’s “How many people” tool for an estimate of how many disabled users you can expect for your product.

Often this thinking is a result of an assumption that people with disabilities don't use the internet - certainly not blind users who surely cannot see the screen? It is also likely due to a narrow view of what conditions are within the scope of accessibility, and thinking it won't include users with cognitive or degenerative conditions, users with low vision or colour blindness or older users.

The hidden nature of many conditions

What people may mean by “none of our users are disabled” is that they’ve never heard of a user who explicity stated they were disabled use their product. Why would they? Many people keep their disabilities or conditions hidden, or don’t even see their condition as a disability.

People have adaptations or coping mechanisms which they use to work around their condition which reduce the outward presentation but do not lessen the impact.

Things like screen-readers or page zoom or high contrast mode don’t show up in analytics (nor should they), so they would never know if someone was using assistive technology.

Negativity of poor accessibility

What stakeholders might see is negative reviews about a product because of their lack of accessibility, or alternatively see praise heaped upon a competitor because they took accessibility seriously.

A product with poor accessibility is essentially shouting that they do not care about you as a customer. Why would you give such a company your business, especially when there is an alternative?

As users who need to make adaptations to use digital products are so used to poor accessiblity, when a product is accessible it means that this becomes a straight recommendation. It could even win customers over from a theoretically more capable or cheaper competitor.

If they really don’t have disabled users it is likely be because their product is inaccessible and they are leaving revenue on the table.

The uncertainty of tomorrow

Let's for a moment say that they can be absolutely sure none of their users are disabled. They cannot be sure those same users won’t be disabled tomorrow. Disability is a group which anyone can join at almost a moments notice.

No product can dismiss accessibility because they feel they know their users that well. The truth is they don’t and that knowledge is transitory at best.

“This is an internal product”

I've heard this a lot as a reason for not thinking about accessibilty on internal products. The assumption is that they “know” there are no disabled users on the team which will be using it, so why go to all the effort to make it accessible?

As hinted at above, it is not the responsibility of our users to declare medical conditions when using a site. Accessiblity is not just for publicly-available products. If someone needs to use something as part of their work then they have the same rights as those accessing public sites. Read more about the legalities of accessibility.

All the same arguments apply here as the previous example - you do not know everything about your users and certainly cannot know your future users. This is even more true now as working from home has increased and conditions and adaptations (such as using a screen-magnifier) are less visible.

You also have a duty of care for your staff. For example, you have a small team using an internal product. One of that team develops a condition. Because the product is inaccessible that person can no longer do their job which could lead to a variety of legal and other outcomes.

Deferring responsibility

It is tempting to say that your team does not have the expertise to make a product accessible (we will get to this shortly) and pass all responsibility to the other teams, whether that is the team producing library code or a specialist accessibility team.

Just as with security the specialist teams can help with specific issues or provide the building blocks for good practice, but it is the responsibility of the product team to undertake accessibility as part of the job.

With accessibility there are both long and short term aims, but if no-one is taking responsibility for keeping up momentum then it is possible for the team to fall back into old habits. So it is essential that the delivery leads are keeping an eye on this at least until it becomes embedded in the team.

It is necessary for the whole team to be on board for an effective accessibility strategy and accessibility needs to be incorporated into all the team processes to avoid it being forgotten about.

Read more about team processes and responsibility

Deferring to a code library

It might be that you are using a design system or code library. This can lead to assumptions that if the team uses that, then accessibility will be “inherited” from this. This can be true to an extent.

A design system should be robustly tested for accessibility, but in practice this is usually only done when the components are initially developed. Time, browsers and assistive technology support moves on and unless the design system has a regular testing regime in place, things can slip through.

These components will likely come with some accessibility features, but the team implementing them needs to understand how they help the user. Misunderstanding how a component presents information to a user of assistive technology can lead to those features being misused. For example, a component allows an aria-label to be added, but it is clearly up to the development team to use this correctly and ensure the attribute is actually needed and that content provided is appropriate.

Component libraries also by design need to allow for a degree of flexibiity in how the components are utilised. This flexibility can allow accessibility issues to creep in when implemented in the real world.

Design systems often only have a dozen or so components. Often teams may find they need to build something custom for their project. At this point the team needs to understand how to build that in an accessible way.

A well-built design system component can give you an amount of assurance that what the team is building is accessible. However the structural component is only part of the story. The content used in those components, how multiple components are composed together, the wider page and even wider user journey are all part of the accessibility story and also need to be considered from an accessibility viewpoint by the team implementing it.

Deferring to an accessibility audit

Some companies (and especially government departments) undertake accessibility audits or reviews prior to launching a product. It can be tempting to see this as an opportunity for someone else to do the hard work of finding the project's accessibility issues so the team can fix them, without it getting in the way of day-to-day delivery.

This approach will always lead to either missed deadlines or products launching with multiple accessibility barriers, which will most likely then languish in the backlog. It also misses a valuable learning opportunity for teams to pick up skills (without the looming deadline) during the product development.

A pre-launch review can only be used as part of a wider accessibility testing strategy. By itself it is unlikely to achieve the desired outcome as it sits too close to the launch date and is rarely able to prevent a launch if it finds issues.

Read more about accessibility testing strategies

Assumed cost of implementation

It's interesting that accessibility is one of the few practices which we seem to have to barter for time and budget on. There are so many sites which have had no accessibility process prior to launch and which are now having to face costly remediation.

If accessibility is included in all stages of a project then the actual cost is much lower than what will be seen on a remediation project. It won’t be zero as there is additional time, testing and research required, but the figure is much lower than only tackling it at the end.

It has been estimated that having to fix issues after release can increase cost by 30 times against finding that issue during the design phase. By including accessibility during all stages this rework can be avoided and costs minimised.

What really costs when it comes to accessibility remediation is where the fundamental page design or user journey is found to be flawed. This requires major rework and is not something you want to be doing as a product flies towards a deadline.

Something to bear in mind is that considering accessibility during design and development generally results in a better product. Clearer signposting, more understandable content and other benefits often come out of such accessibility work.

The question then is really can you afford not to consider accessibility?

Assumed impact on deadlines

Just as with the monetary cost, there of course is some additional cost to making a better, more robust, more usable product. Because that is what we are talking about - making the product usable by more people.

Yes the team may take a little extra time to learn new skills, but we need to allow teams to upskill in accessibility just as we might for security, testing or performance. Accessibility is a part of every role's responsibility, not an addition which can be opted out of.

Accessibility isn’t more work, you were just cutting corners before. The work was incomplete.

This may sound harsh but it is true - accessibility is not a nice-to-have for those affected by it, it is essential to being able to use your product.

However, just as with the monetary cost there is a benefit in less rework later on. If accessibility is not tackled as part of the initial development process it becomes harder to prioritise later on as feature releases take precedence.

The more usable product which comes out of accessible design will mean less support tickets from users having trouble with the product. Often the product which results is less complex and so easier to maintain.

In 2016 Slack was using over 130 different colours (including 32 shades of blue).

When an accessibility issue was raised this was reviewed and reduced to just 18 total, making it much easier and more efficient for designers and developers.

The Minimum Viable Product (MVP) paradox

Accessibility is often the first thing sacrificed to deadlines. Too often I've heard “this is an MVP, we'll add accessibility in later”.

Minimum Viable Product. That means a product which has the smallest amount of functionality to perform its required role. It doesn’t mean that you can cut out a whole group of potential users from using that functionality.

What if we left off any cross-browser testing from our MVP? Lets exclude any users of non-Chrome browsers. We wouldn’t do that because cross-browser testing is one of the core tenants of web development (although it seems not always). In the same way accessibility should be part of the core delivery.

Not including accessibilty in an MVP shows that something is lacking in the design and development process. As outlined above accessibility needs to be part of every step. It isn’t something you de-prioritise.

By dropping accessibility to your backlog you are just creating a design and technical debt mountain which in my experience never gets tackled.

If an MVP doesn’t include accessibility then I'm afraid you don’t have an MVP.

With good planning the additional time required for an accessible product delivery should not mean a deadline needs to shift to accommodate the extra work. It will however likely lead to less work later down the line. Remember accessibility work in a project starts before development beings.

Accessibility as a checkbox item

There is a lot of noise around compliance, especially in the public sector. Read more about the legalities of accessibility. This can lead to accessibility and compliance being seen as the same thing. This can further lead accessibility to be seen as a checkbox item - “once compliance has been confirmed we can forget about accessibility”.

This is both incorrect and damaging to ongoing efforts to improve accessibility.

Compliance only measures a site against a predefined set of criteria at a specific point in time. Whilst these criteria are well-meaning they are not comprehensive, nor do they guarantee that a site built to them will be accessible, merely that you have done the least you can do to prevent the worst issues from appearing on your site.

Even a compliant site can have significant barriers for some users and it is only through rigourous testing, including with users, that we can remove most of them.

The checkbox mentality also suggests that once accessibility has been “done” that it can be forgotten about. But accessibilty requires an ongoing approach to ensure future work, for example new features or maintenance updates, do not introduce issues, but also so changes in the support landscape (such as browsers and assistive technology) are catered for.

Read more about testing strategies and accessibility

Reliance on out-of-the-box automation

When it comes to testing for accessibility we too often rely on one-click solutions to tell us if something is accessible or not. Browser plugins such as axe or Wave certainly have their place in our accessibility toolbox, both they should not be the only items in it.

I have often seen teams run one of these plugins and declare the page or component accessible. Whilst it is true these tools are valuable in finding some issues, they cannot find a whole range of accessibility failures (current thinking is they may find around 40% of issues). It is similar to running a code linter and then not doing any unit, integration or end-to-end testing because the linter said it was ok.

We need to utilise a range of different testing methodologies to help us discover accessibility issues.

Read more about improving automated testing

Overlays

There is another aspect of automation and accessibility - the accessibility overlay. This takes the form of a javascript widget which is installed on an already launched site and promises to fix all of its accessibility failings by automatically fixing issues or offering the disabled user different options.

“We’ll use one of those accessibility overlays, they’ll fix everything for us“

Seems a smart choice - bypass all the expense and time by taking out a subscription to an accessibility overlay which will take care of all that accessibility stuff.

Except they don’t work. In fact often they will make things worse for the user.

The European Commission has even weighed in and said they can be harmful:

"... some overlay tools have been reported to interfere with the assistive technologies used by people with disabilities. In other words, overlay tools may make a website less accessible for some users"

European Commission (source)

The European Disability Comission and the International Association of Accessibility Professionals (IAAP) also issued a joint statement against the use of such overlays.

And think about the use-case. If a user needs these adaptations, they are going to need them everywhere, not just on your site. So if they need text reading to them they will use reader software that works everywhere. The solution is not to present the user with a custom solution, but to make the product work with what the user already uses.

Often the overlay just cannot fix what is broken, whether that is poor font-sizing and colour choice or just poor copy design or page design.

Moreover, why should the user have to try to work out how to use the particular overlay you decide to put on your site (and then a different one on the next site)? All an overlay does is shout to the user (and the product’s competitors) that you don’t really care about accessibility.

They are also an expense which would be much better spent on actually fixing the issues with the product.

For more on this see the overlay factsheet.

Lack of support from processes

Even if the team is skilled in accessibility, without a process which supports this work it is all too easy for standards to start to slip. This is especially true as team members rotate out and this can result in just one or two people becoming the only ones maintaining accessibility best practice.

Read more about team processes.

Find out the reason for any pushback

If you come across pushback like the examples above, the first thing to do is to find out the reason for the pushback.

- are they just unaware of the impact of an inaccessible product?

- have they heard accessibility is difficult?

- are they worried as accessibility is something they haven’t dealt with before?

- does accessibility not feature in a key performance indicator (KPI), so drops down in the levels of importance?

- is there a skill gap on the team so no-on knows how to proceed?

Theses are just a few reasons why accessibility is getting de-prioritised on a project and all require slightly different approaches.

A roadmap for accessibility

Just complaining rarely works

Just complaining about lack of movement on accessibility rarely works, but empowering someone to deal with it who was previously had it down as a problem area can lead to them becoming an evangelist as others will then look to them for help in doing the same in their own area.

If your product has accessibility problems sometimes just finding the worst area, fixing it and then demonstrating it and the impact it has to the team and stakeholders can be the first step to getting buy-in. Sometimes a simple before and after showcase is all you need. Even better if you can show a user for whom it caused a barrier which has now been removed.

Fixing a lack of awareness

There are a lot of assumptions around the whole area of disabilities and accessibility. Sometimes you just need to break a few of these to get traction. There is also a general lack of understanding of the simple issues users might be having because people have difficulty in seeing how something might impact a user with a particular condition.

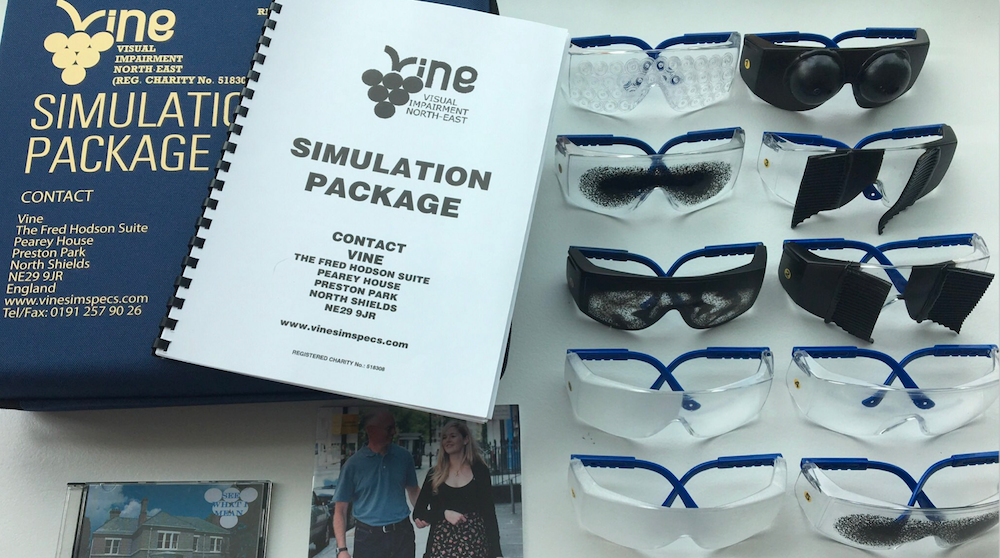

Proctor & Gamble designers were having difficulty getting accessibility taken seriously.

They finally sat stakeholders down with low-vision emulating glasses and asked them to pick which bottle was shampoo and which was conditioner.

When they couldn’t, accessible adaptations to the bottles were finally approved.

Even just taking a screen-recording of how a page sounds to a screen-reader user before and after a fix can be enough to show how important accessibility is. If you have access to UR recordings of users with accessible needs using the product and having difficulties then this is the best thing to show to help unblock accessibility work.

Skill gap

There is no way around it, accessibility is a complex thing. That is why we cannot expect one person on a team be be responsible for all of it. It has to be a team responsibility.

Be aware that implementing code solutions without proper knowledge of the impacts that code may have can actually make things worse. It is always best to give the team time to learn this properly. This also means it is important to ask for assistance where possible if there is a lack of skills on the team. If there is expertise elsewhere in the company, lean on that to help your team.

Look to work with an accessibility specialist, they can provide insight by working with:

- the design team to find accessible solutions

- delivery and product managers to review ticket requirements

- the test team on how best to enforce accessibility requirements

- developers to implement designs without excluding users

However the team cannot come to rely on an accessibility specialist being available. They need to develop their own skills to find solutions to day-to-day issues, perhaps occasionally utilising the specialist for specific and complex problems.

Encourage the team to take time to learn. Just as with any other skill such as security or performance it will take time and this needs to be accounted for in timescales. Use team meetings such as sprint reviews to highlight accessibility wins and discuss issues.

Of course the team might not be able to upskill in everything right away. Look at staging the training.

If the team lacks skills, also look to increase the amount of user testing you are doing with disabled users to help inform decisions.

Present a plan

Sometimes there is an understanding of an issue being present but no understanding of how to go about fixing it. There can be an awareness that there is a large accessibility backlog, but because no-one has taken ownership it is never acted upon. This is a silent backlog - there might not even be tickets created but everyone is aware there is something there which needs to be done.

In this case there is no actual person blocking the progress of accessibility, just a lack of process. There might even be a willingness to get it fixed, but no idea of where to start.

In this case it just needs a plan putting in place to tackle the issue and at least get it on the backlog and in the development cycle.

Build accessibility into team processes

It is important to provide a team with a structured way to help them move toward more accessible practices. Use existing team processes and add accessibility points to each one.

Places where accessibility can be highlighted and potential issues caught:

- design documents

- prototype development

- definition of ready

- code commits / pull request reviews

- testing procedures

- defintion of done

For more detail on how these can be improved see team processes and role-based accessibility.

Start with small wins

Some accessibility improvements require very little in terms of time allocation, for example making sure form fields have accessible names. But these simple fixes can start to drive momentum and provide the team with the morale boost which they might need when facing a new skillset.

Work through the backlog to size issues based on time and complexity as well as severity and pull through groups of the easy wins to keep momentum going.

Keep accessibility current

Always talk about accessibility - include it in demos to stakeholders, reports, meetings. Make it a staple of everyday life in the team so it just becomes part of the furniture. Encourage delivery leads and stakeholders to advocate for accessibility and showcase accessibility wins to ther teams.

Find out what other teams are doing around accessibility and bring that back to the team.

Measuring success

Especially when starting out on an accessibility journey it is important for a team to be able to see progress, especially if they are dealing with a large backlog of remediation issues.

With accessibility being such a diverse and complex subject, how might we go about measuring success? Sure, the number of WCAG issues flagged on a site is one way, but as we have already touched on, compliance is only one aspect.

Here are a list of things we can look at in our backlogs:

- WCAG A/AA issues outstanding - the most obvious thing to track but worthwhile nonetheless

- WCAG AAA issues - whilst not required for general compliance they can be a good indicator of the depth of accessibility and are too often overlooked

- best practice issues - these might be raised as non-WCAG issues on an audit or flagged as best practice on automated tool reports

But we can also dig a little deeper to help improve processes:

- time to fix - keep an eye on the time it takes to get around to fixing any outstanding accessibility issues, perhaps setting an upper limit so items do not fester on the backlog

- new issue generation - we should not be adding issues when we add new features so keep track of why any new accessibility issues are being created and if they could have been caught before shipping

- mapping accessibility issues across user journeys - this can be useful, both to identify problems in processes, but also to identify where a user may be confronted by a series of issues which even if low impact individually can wear the user down to the point they abandon the task

Then there are some more general things to keep an eye on:

- team skills - do all of the team engage in accessibility

- by attending training sessions

- attending user research observations

- being able to showcase work they did to incorporate accessibility

And some user-centric metrics:

- user satisfaction reports (or Github issues) - how many times are accessibility issues raised by users, but bear in mind they might be framed as a usability issue, so some investigation may be needed as to the true cause

- task completion - whilst we cannot know who is completing or abandoning a task we can continue to perform usability testing with disabled users to catch any regressions

Legislation

Sometimes it can be necessary to resort to pointing at the legalities of a situation to get it resolved.

However this is never the preferred way as it invariably ends up in a word-wrangling exercise where exemptions to the requirements are claimed.

Wrap-up

One of the hardest parts of accessibility is getting buy-in from stakeholders and the team. However once they are on board there is still work to do to ensure the momentum is kept up and accessibility becomes a natural part of the process.